Key takeaways

The Guidelines provide companies with clearer insights on how their transactions will be evaluated under China's merger control regime. The Guidelines not only provide detailed and comprehensive guidance, but also include practical examples to illustrate complex antitrust concepts. SAMR's emphasis on ex ante merger compliance encourages companies to assess the potential impact of merger control requirements in China on deal feasibility and timelines at the outset instead of waiting until after signing.

The Guidelines are largely based on SAMR's past enforcement experience and are more aligned with international antitrust guidelines, such as the EU and the US. Businesses engaged in cross-border transactions can benefit from a more familiar and standardized approach in SAMR's merger review process and greater consistency across jurisdictions.

Notably, the Guidelines now include a provision on government subsidy, seemingly in response to the EU Foreign Subsidies Regulation1 and the US Act requiring Disclosure of Subsidies by Foreign Adversaries2. The Guidelines state that SAMR now has the power to request information from transaction parties ("parties") on subsidies granted by governments, and will analyze whether such government subsidies would have any adverse effects on competition in the relevant market during the merger review.

SAMR is also currently working on the Guidelines on the Review of Non-Horizontal Mergers. The non-horizontal merger guidelines will address vertical mergers between suppliers and their customers, as well as conglomerate mergers, which are particularly relevant to rapidly consolidating sectors like semiconductors and technology. The issuance of the Guidelines and the upcoming non-horizontal merger guidelines represent significant steps toward enhancing the reliability and effectiveness of merger control in China.

In depth

Some noteworthy developments under the Guidelines include:

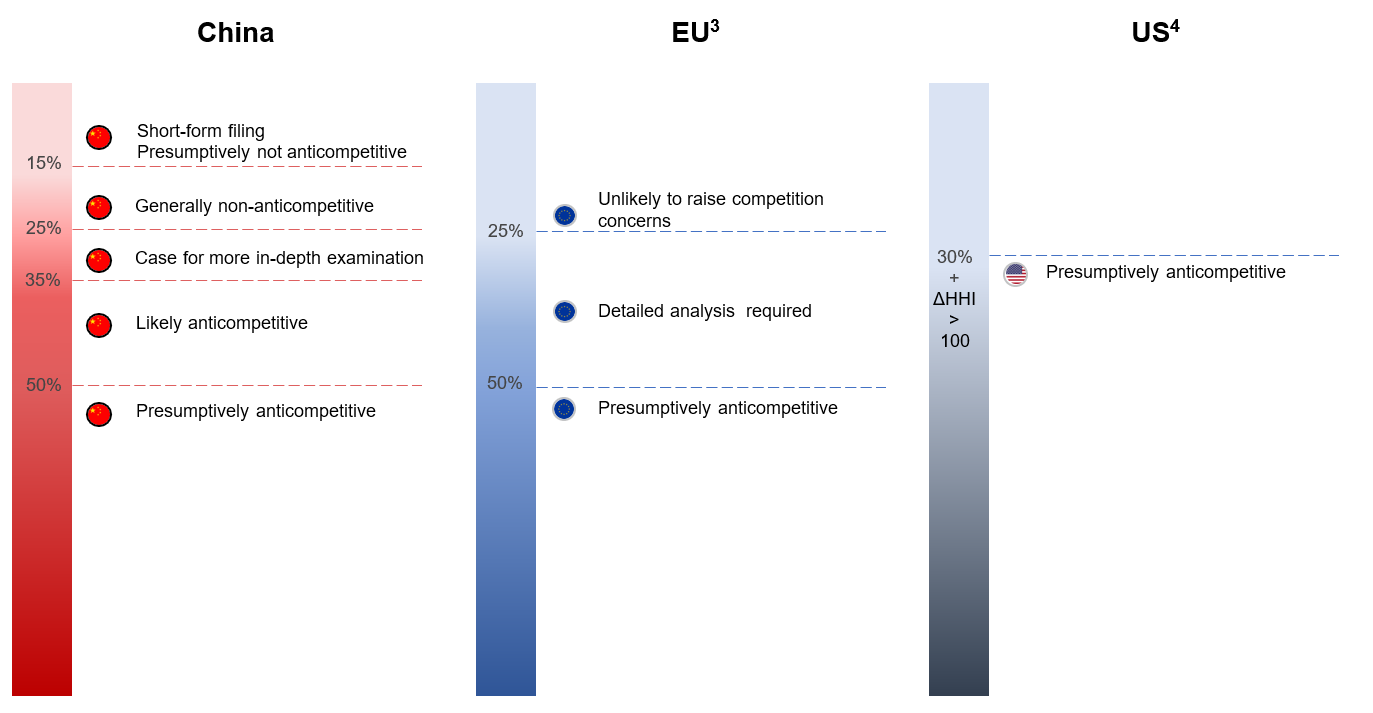

(1) Setting market share and HHI data thresholds for competition analysis

To evaluate parties' market power and the competitiveness of the market(s) they compete in, competition authorities globally tend to rely on quantitative indicators such as market share and the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI).

While SAMR has followed this approach, the Guidelines are the first to explicitly provide the thresholds for market share and HHI that indicate presumptive anticompetitive effects. Compared to international standards, China's more detailed and multi-layered approach enhances clarity and predictability in the merger review process:

Market share

HHI

| |

|

|

|

| Generally not anticompetitive |

|

- HHI<1000;

- 1000≤HHI≤2000 and ΔHHI<250; or

- HHI>2000 and ΔHHI<150

|

/ |

| Likely anticompetitive |

- 1000≤HHI≤1800 and ΔHHI>100; or

- HHI>1800 and 100≤ΔHHI≤200

|

/ |

/ |

| Presumptively anticompetitive |

|

/ |

|

These thresholds help streamline the review process but should not be considered conclusive, given the presumptions could be rebutted by further analysis of competitive dynamics and potential efficiencies. That said, these thresholds provide greater transparency for parties conducting self-assessment and determining their filing strategy.

(2) More flexibilities in market definition

SAMR has traditionally required a precise definition of the relevant market(s) to assess concentration levels and competitive dynamics, which often led to variations in filings across jurisdictions. The Guidelines now introduce a more flexible, EU-like approach: market definition is explored but can be left open, provided the outcome of the competitive assessment does not depend on a specific market definition. This shift is expected to alleviate filing burdens, especially for short-form filings with no significant anti-competitive concerns.

This is not SAMR's first initiative aimed at simplifying the filing process for deals with no significant anticompetitive concerns. As reiterated in the Guidelines, a formal competitive assessment is no longer necessary for deals eligible for a short-form filing, where the parties' combined market share is below 15%.

(3) Consistency with traditional theories of harm

The Guidelines primarily address two theories of harm related to horizontal mergers: unilateral effects (also known as single-firm effects) and coordinated effects (also known as collusive effects), which have been widely adopted globally. These effects may be assessed separately or together depending on the market dynamics, but should be evaluated mainly based on their effects on consumers. If the merger results in higher prices or reduced innovation, it will typically face more rigorous scrutiny unless justified by efficiencies.

- Unilateral effects: This arises when the merger enables parties to unilaterally raise prices or reduce output without requiring coordination with competitors. This includes the scenario where the merger could create a dominant player in the market, thereby significantly reducing competitive pressure.

- Coordinated effects: This arises when the merger creates or strengthens the ability or incentive of firms in the relevant market to coordinate their behavior, potentially resulting in tacit collusion or explicit cartel behavior. For instance, in a standardized product manufacturing sector, a merger that reduces the number of active competitors could lead to price-setting behavior among the remaining firms, particularly in relevant markets where there are high market transparency.

Additionally, SAMR would assess whether mergers might create a barrier to entry by strengthening the parties' market position (even without dominance), thereby making it difficult for new competitors to enter the market or for existing competitors to effectively expand their operations.

(4) Clearer guidance on potential mitigating factors

The Guidelines also set out arguments that may mitigate potential anti-competitive effects arising from horizontal mergers.

- Efficiency: To make use of efficiency arguments, parties should prove that (i) the merger will generate substantial efficiencies (e.g., cost savings, innovation, better product quality), and (ii) such efficiency gains must outweigh any potential restrictive effects on competition (e.g., price increases or reduced choice for consumers). For example, in the technology sector a merger between two competing software firms may eliminate competition but yield synergies that accelerate innovation or reduce the time to market for critical products, thereby benefiting consumers. Parties should provide clear and credible evidence demonstrating that these efficiencies are likely to materialize and will benefit consumers.

- Barriers to entry/expansion: In a market with low barriers to entry or expansion, parties may face significant competitive pressure from new entrants or existing competitors. The Guidelines suggest that the potential harm of a merger in such a market may be reduced. When assessing whether there are barriers to entry/expansion, the relevant considerations include total entry costs, regulatory barriers, technical requirements, economies of scale and access to necessary infrastructure/raw materials. Parties could also provide real examples of actual and/or potential entrants in recent years to support arguments that the relevant market has low barriers to entry/ expansion. In line with the EU and US approaches, only market entries that are proven to be likely, timely and sufficient to outweigh potential anticompetitive effects will be considered by SAMR.

- Countervailing buyer power: Significant buyers (such as large retail chains or other major purchasers) may have countervailing power that can prevent the parties from raising prices or reducing output. The parties may argue that such buyers can exert enough pressure to counteract the harm from reduced competition. For instance, in the pharmaceutical sector, large private healthcare conglomerates or public health systems may have the leverage to negotiate lower prices, mitigating the competitive harm caused by a merger.

- Failing firm defense: If one of the parties is in serious financial distress and would likely exit the market without the merger, SAMR may allow the merger even if it results in reduced competition. For instance, in the manufacturing sector, if one of the leading firms is near bankruptcy, the merger may be permitted to maintain its capacity and protect consumers from supply disruptions. The Guidelines stress that this defense must be supported by robust evidence, such as financial statements and the lack of less anticompetitive alternatives for the distressed firm.

- Dynamic market characteristics: The Guidelines recognize that merged entities, even with relatively high market share and/or HHI data, may not have material anti-competitive concerns where the relevant market is highly dynamic in character. This is particularly the case in fast-changing industries that are characterized by rapid product innovations or technology advancements. Innovation and technological development can be key considerations when conducting competition analysis.

(5) Importance of internal documents

In addition to external evidence collected from industry regulators, trade associations, and market participants, internal documents produced by the parties are also critical for SAMR's review. These documents often provide key insights into the strategic intentions, competitive dynamics, and potential risks associated with the deal. For example, in a healthcare merger, SAMR found that internal documents that discussed pricing strategy, access to market segments, and potential supplier exclusivity clearly indicate the parties' genuine rationale of the deal.

The Guidelines emphasize that SAMR can closely scrutinize internal communications for transactions that might raise competition concerns, such as strategic planning documents, board meeting minutes, and emails between key decision-makers. Statements that could be interpreted as suggesting an anti-competitive motive—such as "this deal is aimed at eliminating a potential competitor" or "without this deal, we will lose our competitive in the eyes of customers"—could be detrimental. These types of statements may unintentionally suggest that the parties intend to reduce competition post-merger, or that the deal is motivated by an effort to undermine future competitive threats.

To avoid statements being misinterpreted (e.g. taken out of context), parties should take extra care in drafting internal documents and communications related to a potential transaction. Neutral language, focused on the legitimate efficiencies or synergies resulting from the merger, should be used.

1 See Foreign Subsidies Regulation, link: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2022/2560/oj.

2 See Merger Filing Fee Modernization Act of 2022, link: https://www.congress.gov/117/bills/hr3843/BILLS-117hr3843eh.pdf.

3 See Guidelines on the assessment of horizontal mergers under the Council Regulation on the control of concentrations between undertakings, link: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=oj:JOC_2004_031_R_0005_01.

4 See Merger Guidelines 2023, link: https://www.ftc.gov/reports/merger-guidelines-2023. A summary of Merger Guidelines 2023 is available here: https://insightplus.bakermckenzie.com/bm/mergers-acquisitions_5/united-states-doj-and-ftc-issue-final-merger-guidelines.

* * * * *

© 2025 Baker & McKenzie FenXun (FTZ) Joint Operation Office. All rights reserved. Baker & McKenzie FenXun (FTZ) Joint Operation Office is a joint operation between Baker & McKenzie LLP, and FenXun Partners, approved by the Shanghai Justice Bureau. In accordance with the common terminology used in professional service organisations, reference to a "partner" means a person who is a partner, or equivalent, in such a law firm. This may qualify as "Attorney Advertising" requiring notice in some jurisdictions. Prior results do not guarantee a similar outcome.